Mncitsini sitting on an environmental health time bomb

By Vuyisile Hlatshwayo

Mbabane is eSwatini’s capital, situated on the picturesque, steep, and rocky terrain of Mdzimba Mountain. In 1992, it was declared a city, an upgrade from a town council to a city council. However, this upgrade further accelerated urban migration for job seekers and urban dwellers who have built low-cost houses in informal settlements sprawling on the city’s outskirts. The Ministry of Housing and Urban Development (MHUD), through the Municipal Council of Mbabane (MCM), stipulates permissible housing structures in the informal settlements.

Climate change-triggered landslides pose a great danger to dozens of Mncitsini residents owning low-cost homes scattered on the mountainside, Inhlase can reveal. As the reality of climate change is beginning to sink in, they live in perpetual fear of landslides caused by the heavy rainfalls and storms wreaking havoc countrywide. Yet, many have considered the symptomatic flash floods besetting the tenants of Mbabane Mall as too distant a problem attributed to its poorly planned location on the floodplain of the Mbabane River snaking through the city.

Scientists say one of the common causes of landslides is heavy rain. As it rains, according to them, water seeps into the ground, percolating into the layers below. There, it can reduce the suction and friction holding together grains of soil or rock, causing the ground to weaken and shift. In his CNN interview, Prof. Dave Petley, an earth expert in landslide management at the University of Hull, said: “Slopes are always trying to reach a stable angle, which depends on what kind of climate they are in. If the climate changes, and rainfall becomes heavier, the slope might now be too steep to be stable, so it will suffer a landslide or a series of landslides to find a new, stable angle.”

Mncitsini is part of the sprawling Msunduza Township, a few kilometres from the city centre. Climate change-induced landslides are troubling low-income residents whose homes are precariously perched on steep and rocky slopes. In an interview with Inhlase, Mbabane East Member of Parliament Welcome Dlamini mentions that during the heavy rainfall, a rock rolled down the mountain and struck a house in one of the homesteads overlooking Msunduza Playground. He is concerned that Msunduza residents may be sitting on an environmental health time bomb.

Ward 11 councillor Themba Malaza, a Mncitsini resident, also discloses that he has received reports from owners of low-cost homes built on the slopes battered by landslides due to torrential rains. He adds that those whose low-cost homes are not yet struck by landslides are unsafe due to the substandard housing infrastructure.

“I received three reports of landslide cases last year from the affected community members after the torrential rains. This badly affected the low-cost structures built with stick and mud or earth blocks, the building materials permitted by the municipality. One of the damaged homes that quickly comes to mind belongs to a Magongo family where a rock crashed into a bedroom during the heavy rains,” he recalls.

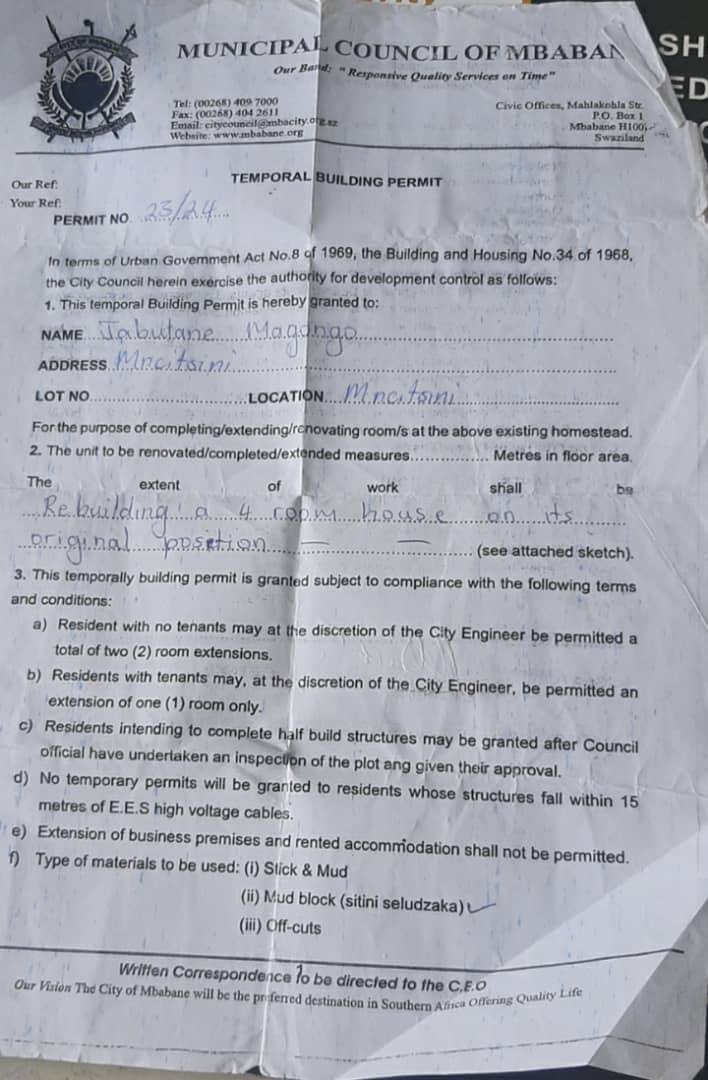

According to Zodwa Khanyile, a Mncitsini community police, there is a steady increase in the low-income homes struck by rocks caused by the landslides after heavy rainfalls in the area. She mentions five cases reported to her. The affected low-income homeowners include Vanana Ngcamphalala of Plot 642, Jabulane Magongo of Plot 814 and Rasta, who, after a close shave with death, decided to go and find safe shelter somewhere else. She highlights that the Magongo family has suffered landslides three times. She also believes the number could even be much higher if other cases had not gone unreported.

“We have been all along thinking that we’re immune to climate change, affecting the tenants of the Mbabane Mall during the flash floods. We thought we were safe because our homes are built on the steep slopes. Lo and behold, we are now faced with the landslides posing a risk to our lives. It’s a pity that the municipality still doesn’t take this problem seriously,” she laments.

Inhlase has traced two Mncitsini landslide victims whose families miraculously escaped death when rocks crashed into their low-cost houses during the heavy rainfalls. One of them, Vanana Ngcamphalala, a security guard working in one of the Mbabane security companies, recounts how he almost fell off a moving van, dazed, when he received a call at 2 am informing him that a rock had crashed into the family’s house. His supervisor let him rush home to attend to his wife and children trapped inside the house.

“When I got home, I saw a big rock that had crashed into the kitchen. Thank God, none of my children got hurt. As it hit the kitchen corner, the wall crumbled and blocked the door, and the window frames and roof bent out of shape. The walls developed some cracks. There was rainwater all over the place due to the leaking roof, wherever there was a nail. We had to squeeze ourselves into one bedroom until the rain was gone,” he recalls vividly.

Ngcamphalala’s low-cost house is precariously located on a steep slope with boulders behind it. Since the rock struck his house, he sleeps with one eye open on rainy days because the remaining boulders pose a high risk to the family and property.

“My children always complain about the danger of landslides whenever there is a sudden downpour. That heavy rain reminded me of the 1984 Cyclone Domoina, which left a trail of destruction across the country. I’ve asked MCM to help divert the water to another route rather than let it continue gushing down to my yard. But MCM has turned a deaf ear. It’s like MCM has ditched us in the area instead of assisting us as ratepayers,” he complains bitterly.

In a similar predicament, the Magongo family has been struck by landslides thrice since 2023. One fateful day at the wee hours, Philisiwe and Jabulane Magongo were awoken from a deep slumber by an alarm raising siSwati cry ‘inyandzalelo’ from the children’s bedroom. They jumped out of bed to check, only to find panic-stricken children with eyes glued to a rock that had crashed into their bedroom. Worst still, their two-year-old grandchild, Temlandvo Khumalo, was buried under the rubble. They frantically launched into a desperate search for the little child to save her life.

“My husband wanted to use a shovel, but I insisted on using bare hands because that would harm the child. I was too relieved when we rescued her, still alive, from the debris. We rushed her to Mbabane Government Hospital around 1 am, where the doctor examined and discharged her because she was well, but only in a state of shock. The collapsed wall left a trail of destruction in the house. It damaged the furniture, including the wardrobes and chest of drawers, leaving us with great expenses,” she says.

The family reported the damaged property to the municipality, hoping to get some relief assistance. But they were disappointed when it did not provide any. The MCM official who came to inspect the damage complained that neither their tractor nor the grader could reach her place due to the narrow road. He then advised the family to write to the chief executive officer requesting relief.

“The CEO did not reply to our letter. Luckily, Inyatsi Construction, where my husband was working, donated us money to buy a chemical called Expansive Powder for Stone from Masoso to break down the rock inside our house. We hired the Toolwire Company to drill holes and put in the chemical to destroy it. After it developed cracks, my husband broke it down with a sledgehammer,” says Philisiwe.

Dogged by misfortune, the Magongos were struck again by another rock caused by another landslide during last year’s torrential rains. As the downpours continued unabated for two weeks, the family heard a thudding sound in the new building under construction. Astonishingly, this also happened in the children’s bedroom. This left the family wondering why the tragedy struck it twice. It then sought relief assistance from the National Disaster Management Agency (NDMA), but to no avail, even though NDMA and MCM have a memorandum of understanding.

NDMA spokesperson Magman Mahlalela explains that the Agency supports affected individuals and communities during disasters, including landslides. He states that the NDMA Act of 2006 provides relief and recovery assistance where feasible. This is based on the scale of the disaster, vulnerability assessments, and availability of resources. He adds that it does not explicitly address managing high-risk areas.

“Under the current legal framework, NDMA does not construct houses in high-risk areas, including slopes, riverbanks, wetlands, road reserves, or other unsuitable locations. When responding to a case where a house in a high-risk area has been destroyed but meets the criteria for assistance, NDMA conducts a thorough vulnerability and safety assessment. We then engage with local authorities, including umphakatsi, to secure an alternative, safer piece of land where reconstruction can be done for the affected household,” he says.

How did the Mncitsini residents end up in the hazardous conditions? Interviewed residents blame MHUD and MCM for settling them in the mountainside, which is prone to landslides. Information gleaned by Inhlase from the Urban Development Project (UDP) 1995-2005 documents substantiates their claims. Through the multimillion World Bank-funded UDP, the Government mandated these two agencies, among others, to implement the low-cost residential upgrading scheme in the informal settlement. This primarily aims to provide basic urban services and housing to low-income people.

When asked about the allocation of plots in the precarious area, Dr. Simon Zwane, MHDU principal secretary, concedes that the topography is a significant challenge to human settlement. The development of brownfields also poses serious challenges, as people cannot be moved far from their original land occupation. He adds that MCM is continuously engaging with the allocated people. He maintains that many problems have been resolved by removing the allocated individuals or improving the flood control.

Additionally, MCM spokesman Lucky Tsabedze absolves the municipality of allocating plots in a high-risk area under the UDP and shifts the blame to the chiefs, district commissioners, and the Eswatini Housing Board (EHB).

“Initially, people settled themselves or were allocated by the chiefs and DCs. MCM inherited these settlements with people living in the environmentally fragile areas (steep slopes and flood plains). EHB allocated the plots when the project began under UPD Phase 1. MCM has not allocated any plots at Mnctsini,” he says, something refuted by MP Dlamini, who witnessed the municipality allocation of a plot to a poor old lady so that the deputy prime minister can construct a house for her.

Asked about the number of reported landslide cases by Mncitsini residents, Tsabedze claims to be unaware of any occurrence in the informal settlements. He points out that MCM has no landslide cases except for land subsidence. He says the land subsidence caused two incidents. One was a rock rolling onto a homestead with no injuries, and another was earth falling onto a homestead below a road. His response is at odds with the reports of the councillor, community police and landslide victims.

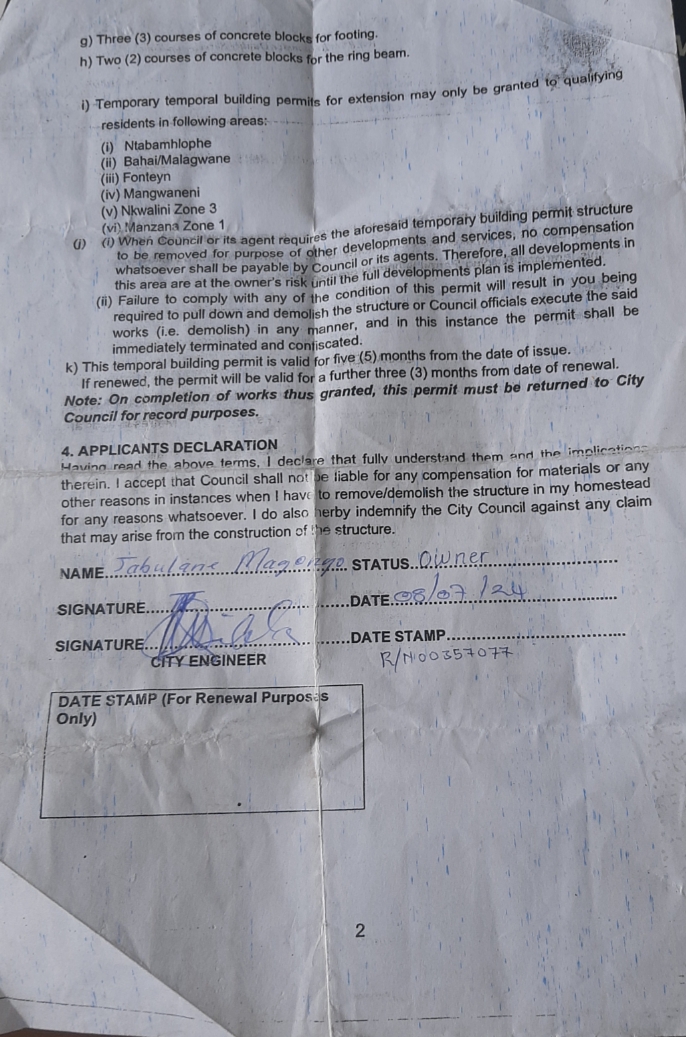

Disgruntled Mncitsini residents also attribute the unsafe housing infrastructure to the municipality’s lowered building standards under the UDP. The city implemented the Building (Grade II) Regulations 1996, requiring residents to build permanent ‘affordable’ homes using either stick and mud or mud blocks (sitting seludzaka). The residents say these building materials are cheap and not strong enough to withstand the intense rainfalls and powerful storms.

However, the municipality spokesperson argues that MCM cannot be held accountable for the collapse of low-cost houses due to the use of cheap and weak building materials. He clarifies that the municipality does not force people to use inexpensive, poor building materials.

“The Council requires that people be settled appropriately and build better houses using proper plans and building materials through the urban upgrading programme. The building ban enforces the building of durable structures through a combination of concrete and stabilised mud blocks as a temporary measure,” he emphasises, but ignores the lack of permanency raised by the residents.

When asked for comment, Eswatini Environment Authority (EEA) chief executive officer Gcina Dladla emphasises environmental considerations when allocating residential plots on steep slopes prone to landslides. He states that the EEA is concerned about mushrooming human settlements on the country’s steep and rocky slopes. He says these areas are highly sensitive, not only in terms of gradient but also prone to high risks.

“Mncitsini, as the name suggests, is a marshy area with a high-water table. If you studied urban planning, you wouldn’t allow human settlement there. But the problem is that the people are already there. We support the municipality’s solution to formalise the townships and deal progressively with the environmental issues. Let’s look at the environmental considerations to mitigate the climate change challenges, like landslides. There are green cities models and approaches linked to climate change resilience and sustainability that our local authorities may consider,” he says.

Councillor Malaza appeals to the Ministry of Tourism and Environmental Affairs and Meteorological Services to educate the communities about the devastating impact of climate change. He complains about the one-day educational workshop instead of a three-day workshop.

“The Mncitsini residents have scant information on climate change because of the weekend half-day training. Most people in the affected areas lack information on the effects of climate change,” he concludes.